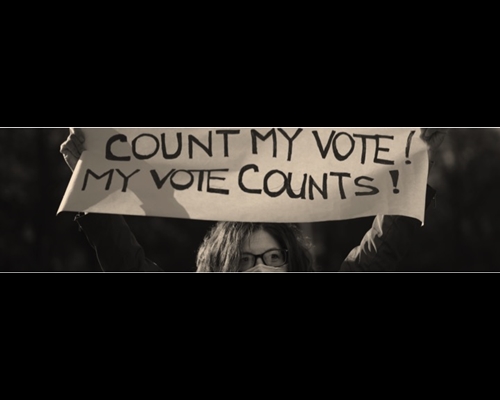

Can you imagine a time when the right to vote was more dearer than the right to have a gun? The ‘universal suffrage’ was the result of centuries of demonstrations, dissent, and even civil wars.

Saji P Mathew OFM

Vote is the most powerful non-violent weapon in a democracy–and that explains,

on the one hand, why it scares and unsettles the powerful and the authoritative

autocrats; and on the other hand, why people still believe and hope in

democracy. It is the vote that demands connection between the most powerful

and the least powerful politically. It is the vote that demands accountability and

answerability from the mighty politicians. It is the vote that forces the politicians,

at least momentarily, to uncouple themselves from the Adanis and Ambanis and

engage with the aam aadmis of our country. Let elections come, politicians and

leaders who seldom are seen among the common folks are found walking,

talking, and eating with them.

Once in five years our country, like many countries across the globe, conducts

the sacred ritual called elections, where every citizen pulls themselves off from

the anonymity of the irresponsible crowd, and self-importantly takes

responsibility for their and their nation’s becoming. Though it is a proud and

satisfying moment for every citizen, the right to vote was not reached without

struggles, protests, and constitutional interventions. Can you imagine a time

when the right to vote was more dearer than the right to have a gun? The

eligibility criteria were more stringent than the eligibility to have a firearm. Even

in early modern democracies, it had belonged only to the white male property

owners. What we call today as the ‘universal suffrage’ is the result of centuries of

demonstration, dissent, and even civil wars.

On 26 April, as I walked to a polling booth situated in an aided school’s tiny

classroom, ironically amidst the skyscrapers of South Bengaluru, I felt privileged

and delighted to be part of a democracy. Though I reached the polling booth five

minutes earlier than it commenced its proceedings, the queue was already

building up with all sorts of people across genders, economic classes, castes, and

religions, standing on the equal ground of one person, one vote, one value. At my

turn, after having my credentials checked at the polling booth I got my left index

finger marked by the purple-black indelible ink, the most photographed ink stain

in the world; I cast my vote on the much debated Electronic Voting Machine,

looked for the light to show up against the candidate’s name and image, waited

for the beep sound, watched the display screen, for the whole 7 seconds,

inspecting my candidates’ name, serial number, and symbol. I cast my vote for

change, exchanged smiles with the booth staff, and walked out hoping that my

vote remains as my vote till 4 June–the day of counting and results.

Political Apathy And Refusing To Vote Defeat A Democracy

If democracy is the most preferred form of government today, it is because of the

possibility it provides for participating in democratic processes; and the biggest

democratic exercise it has is the process it undergoes in electing representatives

from the people and by the people. The least that every citizen can do to uphold

democracy is to go out and vote. “Voting is how politicians hear from their

constituents,” says, Barry C Burden, a professor of political science; and I would

add that voting perhaps is the only way, in a vast and complex country like India

politicians are forced to hear from their constituents.

As per the Indian Constitution, every Indian citizen who is of sound mind is given

a universal voting right. In 1988, in the 61 st amendment the voting age for

elections to the Lok Sabha and to the Legislative Assemblies of States was

lowered from 21 years to 18 years. Elections in modern India have an average of

only 60% voter turnout; the last two phases of the Lok Sabha elections recorded

60 and 61 percent respectively. Is that enough? Almost half the voters have not

registered their votes. It is interesting to note that the major political party

which formed governments in 2014 and 2019 had only 31.34 and 37.4 vote

share in 2014 and 2019 respectively. That does not indicate or constitute even a

fourth of the eligible voters’ choice. It becomes easier for politicians create a

smaller but sure vote bank and remain in power by just keeping them suckled

and happy. The silent majorities who refuse to go out and vote or decline from

voicing their opinion make a democracy less representative of the demography.

Should Voting Be Mandatory?

There are a considerable number of countries in the world where voting is

mandatory in varied degrees. Democracy doesn’t work if a large portion of the

population doesn’t participate. Mandatory voting may seem the best way to

encourage politicians to focus their attention on all, and not just on their vote

bank. Though there have been petitions and pubic interest litigations filed in

India, seeking to make voting mandatory, the court has argued that ‘voting under

the constitution is a right and a choice for people;’ making it mandatory would go

against constitutional freedom and democracy.

Mandatory voting with reasonable provisions does have its benefits too; as an

example, Australia has had mandatory voting for federal elections since 1924.

People who don’t cast ballots have to pay a fine of about $20. As a result, about

94 percent of eligible voters turn out. Because more people are involved in

choosing their representatives, Australians tend to have higher levels of trust in

their government.

An increasing number of the population staying away from the poll booths is a

matter of great concern. When only the usual people vote every time (this was

fought against and universal suffrage came into effect), it is most probable that

we have the same governments with the same agenda and ideologies repeated.

The preferences of those who vote occasionally are probably different from the

party preferences of those who vote each time. Their concerns go beyond party

politics to policies on war and peace, poverty, unemployment, and price hike.

There may be some who genuinely cant go out to vote because of illness, a vast

distance to travel, etc. but we must go beyond naïve reasons of the privileged,

like, I don’t depend on the government, I am protesting, I don't like any of the

candidates, etc. As bad decisions at the polls can result in devastating conflicts,

genocide, damaging laws, and disastrous economic policies; people not going out

to vote allow it even without a contest.

Less trusting people vote less, says, Christopher Federico, a professor of political

science. If you believe that your fellow nationals and government officials are all

out for themselves and cannot be trusted to behave in a moral fashion, then

voting is likely to be seen as useless. Yes. There are times you have candidates to

whom you can’t relate to, like, a rich businessman living in the city or someone

with a criminal background, or a celebrity with the least knowledge of politics, or

even someone who has a generous blend of all the three. But you not voting

would increase the chance of them getting through.

There are lots of things we can care more or less about like, music, cricket,

religion, and so on, but politics must not be put in the same basket. In a world

where we have so little control, and political leaders have every power, how

could you not do that one little thing that you can do? If you aren’t going to do it

for you, then do it for someone else–your parents, a sibling, a friend,

disenfranchised and marginalized, vote for empathy and justice, vote to protect

our democracy and our environment. Voting is so much more about the big

picture than just the present and the candidates that we either love or hate. It’s

about what kind of place you want this country to be in the future.

We talk of a rigged election and are angry about it; but an election where you

don't go out to vote is rigged already. Voting is the first step: well began is half

done towards a functional democracy.