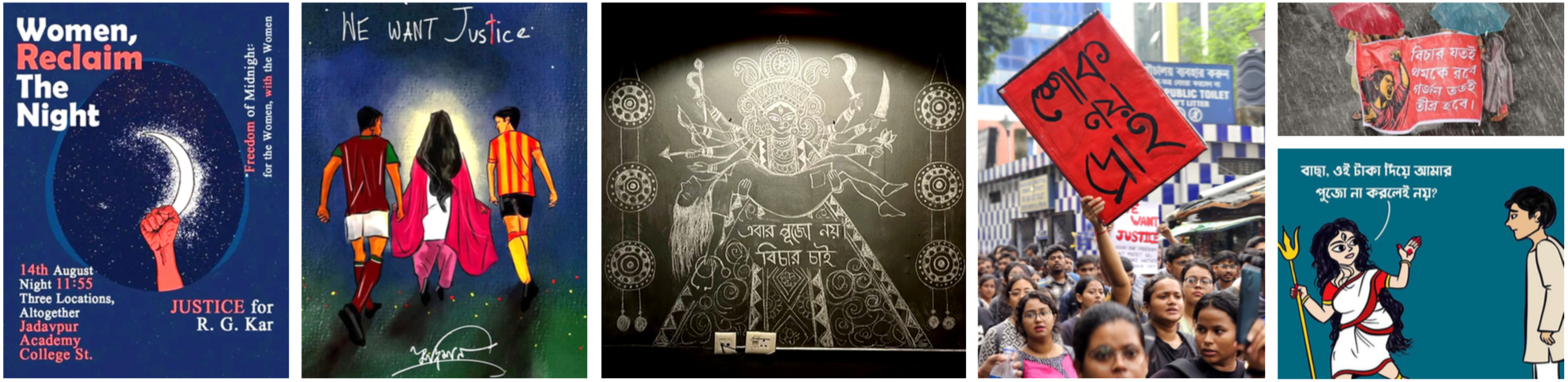

The ‘Reclaim the Night’ movement on August 14 was a significant addition to

the urban Indian women’s movement. This is a critical discourse

on women’s

presence in public life.

First things first. This is not a specula- tion on the horrific rape and murder case of

the young doctor in Kolkata’s RG Kar Hospital. Considering the amount of sordid

details emerging everyday, any public comment on the same would be unwarranted.

Instead, this article intends to decode how the incident has triggered an avalanche

of protest movements and social media discourses, not seen in Kolkata for a very

long time. This is entirely my personal reading of the protests, their social geogra-

phies and their media representations.

Five days after the full scale of the gruesome incident came to public view, streets of

Kolkata burst into a deluge of crowds, angry and impassioned. Kolkata,

a city no

stranger to demonstrations and street marches, was injected with questions,

confusion and disbelief. Something of

this nature, had never happened-not at least

in the social media era-and it struck

a body blow to the dignity of the everyday

bhadralok (the educated elite, a colonial product) life.

A doctor, often considered as

a dhanantwari, or a miracle worker, has a divine status in average Bengali

culture.

In Kolkata-centric Bengali pop culture, a doctor is a hero, selflessly

committed to public service. The double axes of violence- gender and occupation-

took the battle to the heart of the educated middle class. This was personal, and

hence response could be nothing but political.

On the eve of Independence Day, women from all walks of lives, called for a

spontaneous night march: “Meyera, Raat Dokhol Koro”/“Women, Reclaim the Night”.

The poster circulated on social media depicted a clenched fist, a sickle,

a raised

hand , with splashes of red, blue and black. With 34 years of Communist regime in

Bengal, the ideological leanings (not necessarily the political orientation) of the

image, was not to be missed. What we witnessed on the midnight of August 14, was

an unprecedented expression of fury. Kolkata is a humongous city and there was not

a corner where women did not walk their talk.

On its 78th year, the Independence

Day looked bleak and tense, on the streets of Kolkata.

The following day, social media was agog with this language of resistance, forging a

moment of Bengali nationalism. Multiple Kolkata based Instagram handles depicted

drone shots of swirling crowds, raised fists, black clothes, sloganeering and singing-

im- ages that captured the pulse of communal solidarity.

No sooner, the urban

educated elites of Kolkata society—the bhadrolok, the self-appointed cultural

custodian—start- ed dictating the terms of protest on social media.

In Kolkata and

among the well- heeled Bengali diaspora in Europe and in the US, there were

invitations to boycott Independence Day celebrations.

Words like ‘ethics, ‘morals’,

‘conscience’ circulated on Instagram stories, shaming those who ‘dared’ to display

the tricolour on August 15. Tagore and Nazrul (a revolutionary Bengali poet and

Tagore’s junior contemporary) were rampantly quoted, as some posts didn’t hide

their shock that “such a thing could happen in the city of Rammohun Roy and

Rabindranath”. Indeed the city had been tarnished—the image of the city to be

precise—and all the perfumes of Arabia could not sweeten the scent of blood.

On

Bengali news channels, images of Gen Z Bengali kids in California were shown the

kids taking part in parades, singing devotional Tagore songs. At least in the digital

world, a narrative emerged, that all Bengalis must speak in one voice, or at least the

voice in which, Kolkata was singing. This was Bengal Renaissance 2.0.

The optics aside, it must be asserted here, that the “Reclaim the Night” movement on

August 14 was a significant addition to the urban Indian women’s movement.

“Reclaim the Night” originated on the streets of Leeds in the 1970s, with women

protesting against nocturnal crimes. At the peak of second wave of feminism, this

was a critical discourse on women’s presence in public life. As more women started

making entry into professional domain, body politics issues on reproduction,

domestic violence, child rearing, and choice of clothes and make up, gained

currency. No wonder, in his observation on the case, CJI DY Chandrachud, made it

amply clear, that this is as much a movement on women’s right to safety and social

mobility, as it is a case for justice against crime.

In the meanwhile, the August 14 march instigated a succession of demonstrations in

the next seven days, with every possible section of civil society, making sure that

they are not to be left out. This was justified outrage, added to pressure of visibility.

Let us have a quick glance at the genres of community marches unfolding in Kolkata

in the last 10 days:

* Cinema artists and technicians

* Televisions artists and technicians

* Academic arch-rivals Calcutta

University and Jadavpur University

* Singers and radio jockeys

* Football rivals Mohun Bagan and

East Bengal

* Lawyers and advocates (who

wrestled on High Court precinct)

* YouTubers and influencers

* Sex workers

* And of course, junior doctors.

Anger ran in full gusto as each group asserted their individual identities and social

positions.

“Justice for RG Kar” chants rung through the alleys, with unique spins

brought to the slogans. Some samples:

1 . Ebaar Pujo noy, Bichar Chai (We want justice, not Durga Puja)

Ek Hoyeche

Bangal Ghoti, Voy Peyeche Hawai Choti (United stand Bengal, post-partition

Bengali refugees, Ghoti-natives of West Bengal/so tremble the sandals

(footwear worn by the Bengal CM)

2 . Cinema parar eki swar /Justice for RG Kar (Cinema commune sings as one-

since cine artists in Bengal are divided by their loyalties to political parties)

Sit-ins included guitar strumming, Paul Robeson songs, Pete Seeger songs, street

theatre, candle lighting and flash lighting. After a long time, Kolkata found a moment

of reckoning. Unemployment, political extortion, bad traffic-every crisis mounted to

the storm’s eye.

No neighbourhood wanted to be left behind, in their creativity, and

while there has been solidarity, there is oneupmanship too. Graffitis, street arts and

witty banters have contributed to the growing body of verbal and non-verbal

resistance.

As we wait for CBI to further the investigations, political muckraking is on the

uptake. Finger pointing and blame game has started. Civil society has no choice but

to take recourse to these expressions of frustration.

Take it or leave it.