Every politician, when he leaves office, ought to go straight to jail and serve his time,

thus goes an American folk saying. Politics and politicians have come to be

synonymous with dishonesty, favoritism, and corruption. This perhaps is the underlying

reasoning for many good and competent people to stay away from active politics; and

many corrupt and incompetent people to get attracted to active politics. The good

people’s silence and inaction make it easy for the wicked people to fill the world with

their opinions, lies, and propaganda; and establish their agendas and actions as normal

and standard. For Gandhi, being political was not a choice, but an imperative. He

famously said, “Anyone who says they are not interested in politics is like a drowning

man who insists he is not interested in water.”

Gandhi returned to India on 19 December 1914, after his sojourn in England and South

Africa, as quite a matured man of forty-five, having seen the worlds of exploiters and the

exploited. In the heart of the empire where the sun never sets, he must have seen the

normalcy of white supremacy, privilege, and entitlement. In the South Africa of racial

discrimination, being a man of color, Gandhi must have experienced what it means to

be with less or no rights, underprivileged, and treated without respect. Gandhi plunged

into the Indian freedom struggle with half a dozen keywords: satya, ahimsa, satyagraha,

sarvodaya, swaraj, and swadeshi. Recently in a session I was attending, Bobby Jose

Kattikad, the speaker, said, as we arrive at our 40s, we also arrive at the keywords that

define us. From the media content that we read and watch, our conversations, our

engagements, our preoccupations, and the causes that we commit to, others around us

can recognize it. Gandhi was 45 when he came back to India, and he had his

uncompromising keywords to elaborate his life on. Though Gandhi had revised his

opinions from time to time, his conceptual framework remained the same. He had not

altered from his basics. After seven years, he unceremoniously exchanged his pair of

pants, shirt, and suit as a barrister for a dhoti and a towel at Madurai. Should we not be

serious about the politics of a man clad in dhoti and a towel, and steadfastly upholding

satya, ahimsa, satyagraha, sarvodaya, swaraj, and swadeshi?

India’s Political Centre Ought to Be Gandhi

Left, right, and centre are terms used to describe different positions on the political

spectrum. The terms left wing and right wing originated from the seating arrangements

in the French National Assembly during the French Revolution (1789). Supporters of the

king and the traditional social order sat on the president’s right side. These were

generally considered more conservative and resistant to change. Supporters of the

revolution and those advocating for a more egalitarian society sat on the president’s left

side. These were seen as more progressive and willing to challenge the status quo.

Over time, these seating positions became symbolic of broader political viewpoints. The

terms “left” and “right” were eventually used to describe the entire spectrum of political

ideologies.

Left Wing focuses on equality, social justice, and reform. Left Wing ideologies generally

believe in reducing economic inequality and increasing government intervention in the

economy to achieve social goals. They hold on to values such

as freedom, fraternity, rights, progress,

and internationalism. They, with their enthusiasm for immediate social and political

change, can easily move towards far left because, in the words of Ferdinand Marcos, “It

is easier to run a revolution than a government.”

Right Wing focuses on individual liberty, tradition, and limited government intervention in

the economy. Right Wing ideologies generally believe in free markets, minimal

government regulation, and a strong national identity. They hold on

to order, hierarchy, duty, tradition, and nationalism.

Centre focuses on finding a balance between left-wing and right-wing ideas. Centre-

right and centre-left ideologies aim for a mix of social welfare programs and economic

growth. They hold on to values such as pragmatism, negotiation, and participation.

India, the world’s largest democracy, boasts a vibrant political landscape. In the Indian

context, though many may disagree and disown, it is proper and beneficial to consider

Gandhi and his non-violence (ahimsa) as the political centre; because at the extreme

right and at the extreme left, we see the use of violence as a chosen means to achieve

their goals. Along with Gandhi, Nehru was centre-left and Patel was centre-right. The

Indian National Congress was a left-leaning socialist organisation as it fought the

British, but post-independence, the Congress party has also exhibited tendencies of

right wing.

The Dangers of Far Right Going Too Far

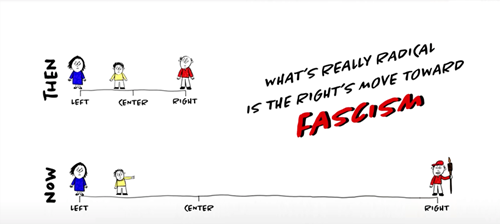

India, more than ever before, must take the political position of Gandhi seriously, for

India today exhibits a dangerously strong tendency towards the far right. Though

extremes exist, the liberal left hasn’t moved much, or they are more under control of the

state. Robert Reich, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley,

says the right has become more extreme over the last 50 years. Some have gone so

very far that they have lost sight of the centre. As Robert introspects, he realises that in

the last 50 years, he, being one from the centre, has moved further to the left of center

without changing his political views at all. How? The right has moved far right and has

moved dangerously close to fascism.

“Far right extremism is a global problem; and it is time to treat it like one,” says Heather

Ashby. Right- wing extremists pose the danger not with bombs but with ballots, says

Daniel Byman. From Brazil to the United States, France to India, right-wing extremist

ideas and groups are posing a grave threat to democratic societies. For example, in

India, the ruling party, after they came to power in 2014, has brought extremist ideas

into the mainstream, advancing the idea of India as a Hindu country irrespective of its

great diversity.

Check Where We Stand

Far right begins with a strong “us versus them” mentality, and belief in the supremacy

of, or at least strong loyalty to, a political, religious, social, ethnic, or other grouping, or

to a person. The group’s survival is therefore contingent on hostility towards and

suppression of those who are outside the group. Far right eventually moves to radical

right, and then to extreme right, with violence as an accepted means to social change.

One begins with racism and micro-aggressions, like belittling jokes, stereotyping a

community or group. Then one moves to religiously or ethnically motivated verbal,

online, and physical harassment and abuse. After which one begins hateful extremism

with coordinated online and offline campaigns aimed at creating hateful and

discriminatory attitudes. Finally, one arrives at violent extremism, advocating terrorist

vandalism, attacks, and assault.

As we strive for a more humane, less violent, and more civilised existence, the life and

inspiration of Gandhi and his unwavering commitment to ahimsa continue to inspire,

guide, and centre us.