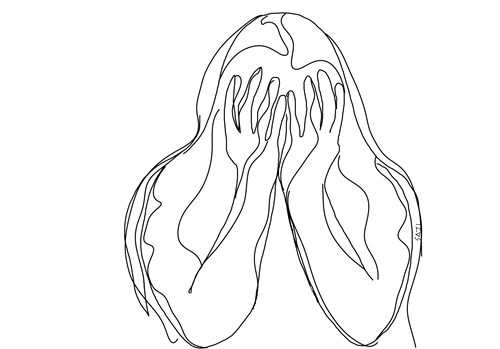

Everyone wants the perpetrators to meet hurried medieval executions

to

satisfy a meaningless closure that

does the least in proving to be a deterrent.

The public sentiment between such sexual offences

is the resignation that

things will never change.

The aftermath of the sexual violence witnessed in Kolkata and Thane

are not the

first to prompt pubic outrage. The Justice Varma Commission Report was the result

of a similar outcry following the gang rape and murder of

Jyoti Singh, a 22-year-old

physiotherapy intern, in Delhi on December 16, 2012. In

29 days a comprehensive

630-page report was submitted to propose amendments to the criminal laws in

India. Consequently, the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 popularly referred to

as the Nirbhaya Act drew criticism of insufficiently adopting recommendations of

the Justice Verma Commission Report. The report that was completed in good

speed, was unfortunately hurried in parliament and in no time public memory

rushed on to other things.

A year later two gang rapes took place in Mumbai at the abandoned Shakti Mills. An

18-year-old girl was gang raped on July 31, 2013 and

a 22-year-old photojournalist

intern was gang raped while her male colleague was restrained

by the offenders.

She was threatened with making

photos and videos of her

rape going public if

she

dared complain to the

police. The accused were

convicted of rape, three

of

them were awarded

death penalty. In 2015,

two teenagers were gang

raped and

murdered in

Budaun district of Uttar

Pradesh, the two were

found hanging from

a tree the following day.

Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) filed a closure report

stating there was no evidence of gang rape, but in 2015 the POSCO court rejected

the CBI’s report. On June 4, 2017 a 17-year- old girl was gang raped and murdered; a

Bharatiya Janata Party MLA was convicted of rape and also the murder of the

victim’s father in judicial custody. On November 27, 2019 there was another gang

rape and murder of a 26-year-old veterinary doctor, whose body was then crudely

burnt. The accused were arrested and were killed by the police in an encounter on

December

6, 2019; this sudden news drew popular praise from the public across

the country. There were literal celebrations held at the killing of the accused saying

they deserved to die like that. On September 14, 2020 a 19-year- old girl from

Hathras, Uttar Pradesh was gang raped and succumbed to her injuries.

Her corpse

was then unceremoniously cremated in secret by the police in the early hours

September 29, 2020; the same day another 22-year-old girl from Balrampur, Uttar

Pradesh was gangraped, her legs broken and sent home in an autorickshaw, she

succumbed too. This year on August 9 a trainee doctor was raped and murdered in

the RG Kar Medical College and Hospital in Kolkata; four days later in Badlapur,

Thane, it was reported that two four-year-old girls were sexually assaulted by a

male attendant in the school wash room. In Kerala, the Justice Hema Committee

Report that was submitted in 2019 was made public on August 19 this year.

Following the charges of abduction and sexual assault filed by film actor Bhavana

against Dileep, a film actor and producer—the Justice Hema Committee was

constituted. Dileep was arrested for a while and now the case is put on hold. There

are many other cases of rape that have not been mentioned here.

The Justice Verma Commission and the Justice Hema Committee were two concrete

outcomes of public outcry. Both outcomes came in to honour timing, they happened

fast but did everything possible not to hurry the process. Although these processes

are not proportionately met with the genuineness of public memory, knowledge and

impulse, it still wields

the historic power to shape the course of building a safe and

accountable criminal justice system. In the heart of the larger public outcry,

meaningful protests

are outweighed by relentless rhetoric

of answering violence

with violence. Everyone wants those perpetrators to meet hurried medieval

executions to satisfy a meaningless closure that does the least in proving to be a

deterrent. Public sentiment between such sexual offences evolves into a collective

resignation that things will never change and therefore, mind one’s own business .

During this time, most girls and women are educated to carry pepper sprays, return

home early or just remain homebound and stay away from a potential situation of

sexual offence (whenever or where ever it may strike).

The men, well nobody

really knows what they are given to understand, but most of them are easily

offended by women (whom they feel) threaten their general knowledge of violence

against women. So now, in addition to women trying to avoid sexual assault, also

need to massage the threatened consciousness of these men by saying ‘not all men’.

The truth of the matter is that this battle has been consistently addressed by

feminist movements in our country for decades. They look beyond public rhetoric to

strengthen the criminal justice system in addressing sexual offences that do not

attract the blessings of public outrage. They identify the pragmatic role of a

sustained response as opposed to the reactionary thrust of the hurried pleasures of

a banana republic.acts of violence that lead up to the impunity of sexual offenders.

The fight against sexual assault cannot be seen in isolation. There are several other

acts of violence that lead up to the impunity of sexual offenders.

When their impunity

is not developed from hurried reactions, how much more must we saddle

the responses born out of meaningful protests to bring justice to them. While we

cannot avoid public outrage fuelled by despair and helplessness, it is important to

preserve the sanctity of empathetic protests. I do not know if there are measures for

these things that I have mentioned, but I do believe

that sustaining the potency of a

response can serve as a much needed compass in observing public outrage.

May we harness the power of public outrage in an amnesia driven society that is

obsessed with fanatic reactions, when it needs more of a committed response to be

healed.