What does one do when one’s compassion cup goes dry and empty; when one

comes to a point where there is nothing more left to give?

I lost my mother very recently. She was 93. For the last two and a half years, she was

ill, and for the last one and a half years, she was bedridden. Though all her children,

when they visited her, used to be generous in taking care of her needs, it was my

brother and his wife who took care of her day in and day out. They did an amazing

job; they regulated their daily routine to make sure that mother did not lack

anything, they sacrificed their possible travels and outdoor fun activities to make

sure that there was someone with mother always. As days passed, weeks passed,

months and years passed, I could see exhaustion and a certain level of irritation

setting in with them. There were feelings of helplessness and powerlessness in the

face of distress and pain, for medically they could do nothing more for mother,

except to give palliative care. Other siblings, especially my sisters, increased their

frequency of visits, and they remained at home for longer periods of time, giving my

brother and wife a little respite.

Leave my family there; imagine you are someone taking care of your old parents

or

grandparents for a prolonged period of time, or taking care of a child at home with

chronic illness, or a child with autism or other mental health issues, or trying to

understand a partner who has given in to addictions, or helping and being with a

friend who is in a toxic relationship for a long time, or simply having very

demanding and entitled children, and you place their needs first. Gradually you

begin to feel overwhelmed, feel exhausted and tired; and come to a stage where you

can’t take it any- more. People can get tired of caregiving or showing understanding

or compassion—it is called compassion fatigue.

Though com- passion fatigue was

identified and written about by Carla Joinson, who herself was a nurse and a writer,

in 1992, this is a phenomenon that got noticed especially during the Covid-19

pandemic. As the pandemic hit the world wave after wave; nurses, medical

practitioners, volunteers, firefighters, police, pretty much everybody in the business

of caring began increasingly growing tired. It is a physical, emotional, and spiritual

exhaustion. One comes to a point where there is nothing more left to give.

We are all potentially vulnerable to compassion fatigue. It happens because of

prolonged exposure to the emotional and psychological needs of others. All empathy

is used up; one’s empathy cup, compassion cup goes dry, goes empty, one loses one’s

capacity for compassion as one used to have. People live in denial of compassion

fatigue for a long time. We may feel tired, irritated, etc., but we have been the helper,

playing the role of caregiver for long, so we go on, we don’t acknowledge that we are

tired.

Juliette Watt, who herself was a victim of compassion fatigue, while narrating her

life story in a TED talk, gives a few symptoms of compassion fatigue: irritation and

frustration, feeling absolutely worthless and terribly sad, isolating yourself from

everyone around you including your own family, reduced feelings of empathy and

sensitivity, and nothing making sense any- more. People can behave mechanically

and become more and more task-focused and less emotion-focused.

What do we do when we reach this stage of compassion fatigue? Just ignore our

duties of caring and showing empathy? Acknowledging that one is tired, burned out,

and exhausted because of caregiving

is important because it not only gives the

caregiver an opportunity to cope with it and rejuvenate but also ensures the person

receiving care does not suffer because of the exhaustion of the caregiver.

How do we refill our cup of compassion? If you are in the business of caregiving,

recharge your batteries daily. Spend plenty of quiet time alone. Engage in what you

enjoy doing—perhaps your hobbies. A regular exercise routine and good sleep can

reduce stress and help you re-energize. Traveling gives lots of oxygen for your

depleted empathy cup.

The ability to reconnect with a spiritual source and practice mindfulness meditation

are excellent ways to ground yourself in

the moment and keep your thoughts from

pulling you in different directions. Commit to eating healthily and better; and stop

all other activities while eating.

Spend time with family and friends who give you positive vibes. Hold one focused,

connected, and meaningful conversation each day. This will jump-start even the

most depleted batteries.

Ask for help. Assuming that no one will help could be wrong. Connect with people;

speak to them about what is happening with you. Caregivers deserve care against

compassion fatigue.

Compassion fatigue is real. Sadly, it happens to good people, people who care. We

need them to continue works of compassion. We must step in when we see people

facing compassion fatigue. When we visit the sick around us, which is a good thing

to do, we must also visit the caregiver, speak

to them, and be of help to them if

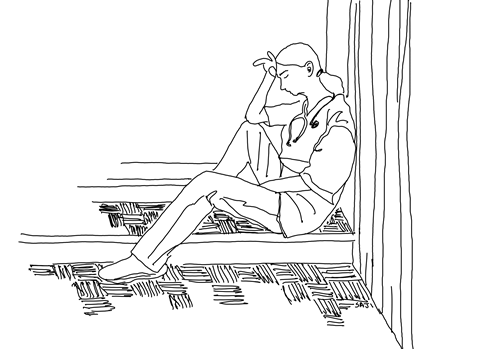

possible. The Migrant Mother (the image on the August cover), by photographer

Dorothea Lange (1936) ex- presses compassion fatigue. It is the image of a mother,

aged 32, and her children who were victims of a blighted pea crop in California in

1935 that left the pickers without work. This family sold their tent to get food. This

image embodied the hunger, poverty, and helplessness endured by so many

Americans during the great depression. Children are constantly in want, how long

would her cup of compassion last?